Developers Beware: the rule in Harris v Flower [1904]

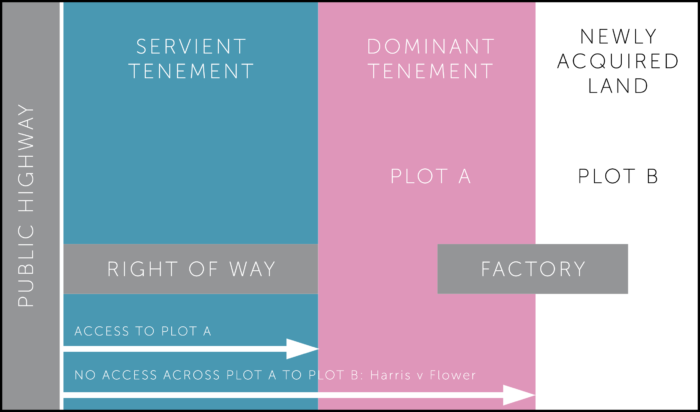

It is, unfortunately, an often overlooked principle of English land law that, although you may have a right of way over someone else’s land to part of your land (Plot A), you cannot rely on that same right of way to get to another part of your land (Plot B, even though it adjoins Plot A), that is not expressly covered by that right of way. This rule was laid down in the 1904 Court of Appeal case Harris v Flower CA [1904] which states (more simply) that if you have an easement providing a right of way to access Plot A then you are not allowed to use it to access Plot B. Please see the illustration below. The logic behind the principle is that you cannot increase the burden of user over the right of way beyond that which was originally contemplated when the right was granted. Extending the land area to an additional plot is presumed to increase the use of the right of way, an additional burden which would not have been in the original contemplation of the parties. The principle against enlargement of the original right granted and excessive use (such as the increase in use of service media, drains, wires and the like) are not looked at in this article but are doctrines that apply to other kinds of easements, which developers should also be alive to, when undertaking development projects.

In the case of Harris v Flower, the servient land-owner (Harris) alleged an excessive user by Flower, which attempted to impose an additional burden on the servient land in the use of a right of way for obtaining access to a factory constructed partly on the land which expressly benefited from the right of way (‘the pink land’) and partly on other land (‘the white land’). In addition, Harris claimed that the right of way had been abandoned, as it was practically impossible to separate the lawful original user from the additional excessive user, and thus the original right of way could no longer be used at all.

Held: Harris’ appeal, based upon the latter claim, failed. There had been no abandonment of the right; but the user of the way for access to the buildings so far as they were situated upon land (Plot B) to which the right of way was not originally granted, was in excess of the rights of Flower. The use of an easement cannot be extended, beyond the scope of the grant, to impose a burden greater than that which the servient owner agreed to accept. In other words, a right to pass over land to reach plot A cannot be used as a means of access to plot B, unless it was so used at the time of the grant.

Giving the leading judgment, Vaughan-Williams LJ said that the uses for the additional land: ‘cannot be said to be mere adjuncts to the honest user of the right of way for the purposes of the pink land . . . It is not a mere case of user of the pink land with some usual offices on the white land connected with the buildings on the pink land.’ In addition, he noted that the use of the factory would increase the amount of traffic over the right of way beyond the level permitted by the grant: ‘This particular burthen could not have arisen without the user of the white land as well as of the pink. It is not a mere case of user of the pink land, with some usual offices on the white land connected with the buildings on the pink land. The whole of the object of this scheme is to include the profitable user of the white land as well as the pink, and I think access is to be used for the very purpose of enabling the white land to be used profitably as well as the pink, and I think we ought under these circumstances to restrain this user.’

More recent cases have affirmed that the rule in Harris v Flower prevents an easement being used for an additional plot of land, unless that land is used for a purpose that is purely subsidiary or ancillary to the use of the land that originally had the benefit of the right when the right was granted. This might be termed the exception to the rule.

Whether the exception to the rule in Harris v Flower will apply will very much depend on the facts of the case; so developers should still be mindful of the rule when assembling sites for development. If available, title indemnity insurance may be needed to cover the lack of right of way to additional plots of land, or the owner of the servient tenement could be approached to formally agree an extension to the right of way. But note that the two courses of action are likely to be mutually exclusive, such that indemnity insurance will not be available if the servient land owner has been contacted. Indemnity insurance may be the better option.