Health and social care is a sector defined by resilience. Partially through choice and partially by larger forces at play, managers, workers and stakeholders alike are required to show incredible strength of character and ability to bounce back from whatever challenges are thrown at them.

However, the pandemic put even more strain on that resilience.

Unimaginable difficulties have been thrust upon the care sector in the time since March 2020, and as we now emerge from the storm, the sector is evaluating the damage done to the status quo. Though, as the sector recovers, a once in a lifetime opportunity is presented to change service provision for the better.

For this report, we have spoken to care experts, managers and professionals to surface meaningful solutions as to how the workforce that has been under immense pressure can be reinvigorated and supported. We explore how providers can plug the employment gaps that have formed during the pandemic as many workers left for other industries or were even pushed out.

We also investigate how funding and regulation still present difficulties that will only be possible to navigate with systemic review, political impetus, and local governmental support.

Despite the difficulties, the sector is emerging from the pandemic and there are opportunities to enhance and develop the strides the sector has made in embracing change. The technological advancement and innovation the sector has needed to commit to at pace will lay the foundations for future opportunity.

Mei-Ling Huang - Partner, Social Care, RWK Goodman

We would like to thank those who have contributed to this report and welcome you to join the discussion via the activities we have planned over the coming months.

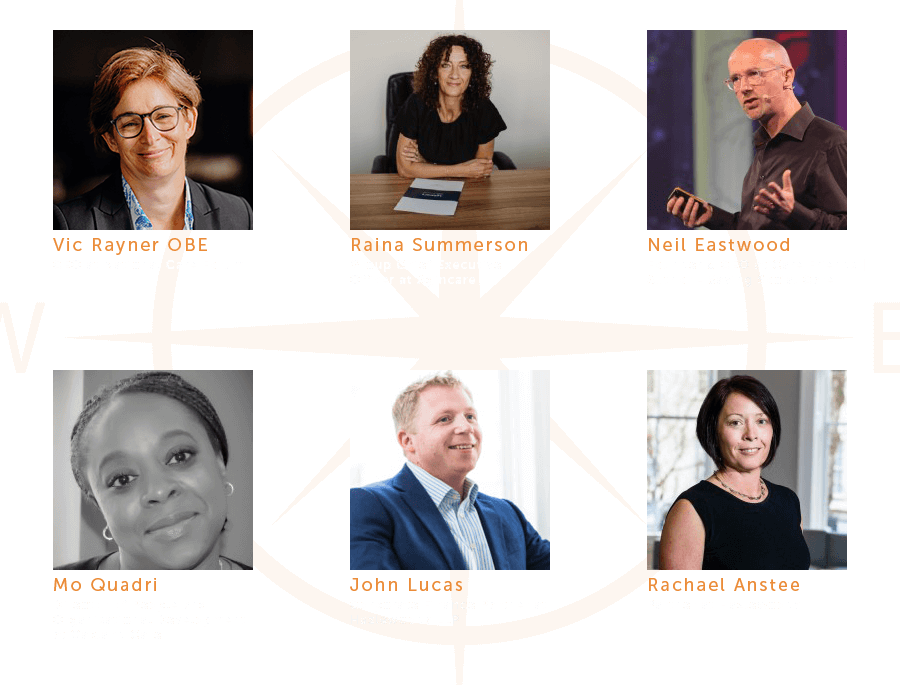

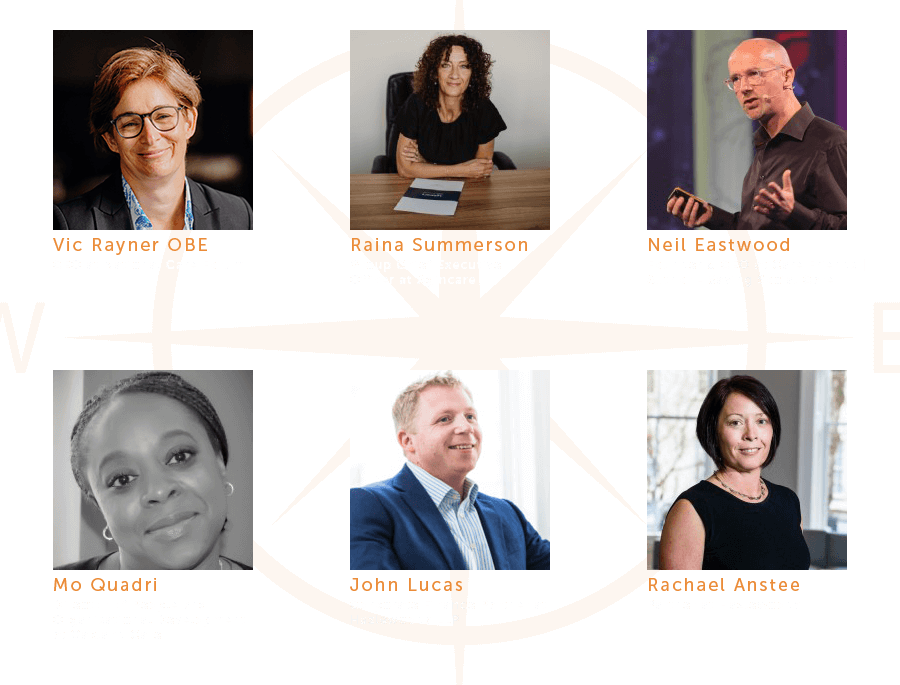

Thank you to our panel of expert contributors

Thank you to our panel of expert contributors

Be part of the conversation by joining James Sage, Hazel Phillips and Mei-Ling Huang and other sector experts in our Emerging from the storm – the reflection series:

Podcast – Crisis Management in Social Care – featuring Charlie Jones of BKR Care Consultancy and Nathan Hollow of PLMR

Podcast – Social Care Insights – featuring Sophie Chester-Glyn of Coproduce Care

Webinar – Recruitment and retention – How to become an employer of choice and reduce staff turnover

Webinar – Data vs personalised care – are they mutually exclusive?

Podcast – Integrated care – does M&A play a part in the recovery?

Emerging from the storm

Chapter one

Retaining a tired workforce – reinvigorating teams

Social care providers have had a challenging period, not just from a business perspective where they have had to pivot quickly to new ways of working and increased levels of health and safety considerations, but critically from a workforce perspective too.

Front and centre of this has been workforce fatigue. Throughout the pandemic, the toll on the social care workforce has been widely reported. Providers have commented on the incredible lengths that their staff have gone to and the pride the sector felt battling through an incredibly difficult period. That said, now that the emergency period is less pronounced, providers are seeing the underlying stress of the experience coming through. Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development at Oakland Care, has seen a step change in mental health issues across the sector and has noted an increase in sickness and “people resigning because they can no longer take the stress.”

58% of health and social care workers met the threshold for a mental health disorder and 22% met criteria for PTSD.

The fatigue the sector has been reporting is evidenced by the ‘Frontline-COVID study’ by the UCL-led COVID Trauma Response Working Group that found that after the first wave of COVID, 58% of health and social care workers met the threshold for a mental health disorder and 22% met criteria for PTSD .

This pressure on the workforce is exacerbated by economic considerations which have grown more severe in recent months with inflationary increases. There is a growing recognition that workforce “distress is around finances” (Neil Eastwood, CEO, Care Friends), with a significant increase in living costs, particularly energy, food, and petrol costs. This is borne out by the findings of the Care Workers Charity Impact Report (2021) which reported that “daily living costs still remains the most frequent use of our grants with 47% using the grant for that reason.” Economic pressures are adversely affecting attrition rates, with many workers looking at alternative careers to make ends meet. Raina Summerson, Group CEO of Agincare feels that “clearly the biggest headache for many operators is attracting and retaining the right staff and not losing them to hospitality and retail.” Whilst care staff are motivated by a myriad of factors including a sense of pride, giving back and a meaningful profession supporting people, the inability for care providers to compete on pay with the likes of Amazon, who are offering large sign-on bonuses and higher rates of pay, poses a real challenge to retaining staff. Recent reports indicate that some providers are trying to compete by increasing pay rates, one example being Vida Healthcare which announced a 30% pay rise taking hourly rates for care assistants to £12.32. Others have announced commitments to pay the Real Living Wage.

Clearly, the Government’s mandatory vaccination ‘experiment’ on the care home sector has not helped with retention. The impact of mandatory vaccinations is stark, with an estimated 40,000 workers leaving the sector at a time when recruitment and retention was a significant challenge. It was particularly damaging that the policy was not introduced to homecare services and the NHS at the same time, as unvaccinated staff left care homes to join those sectors.

Creating a positive cohesive workplace culture where staff feel valued and that they have a voice is critical.

This is further compromised by high levels of care home manager resignations, citing that they too are exhausted by the pressure and legal responsibilities that come with the role due to an ever-increasing focus on regulatory and inspection led agendas rather than focussing on care.

Despite the backdrop of increasing pressure on retaining staff in social care, Vic Rayner, CEO of the National Care Forum is quick to point out that “these are not new issues but clearly they’ve been highlighted and exacerbated over the last couple of years”. Staff attrition has had an operational and cost impact for providers and agency and recruitment costs have soared. The impact has been significant, with some providers needing to suspend care home admissions or hand back homecare contracts because they cannot recruit enough staff to run services safely.

The workforce pressures are also causing many independent owners involved in social care to reconsider their business investments, taking stock from the emergency of the pandemic to understand their business prospects and the future of the sector. Anecdotally we are hearing of provider owners who are as equally fatigued as workers. Whilst they couldn’t exit during the middle of COVID (nor indeed wanted to), John Lucas, Director at Hazlewoods, feels that “over next 12 months there will be a lot of people thinking that they want to exit.”

Mei-Ling Huang - Partner, Social Care, RWK Goodman

Despite these challenges, social care is “essential infrastructure underpinning the health and wellbeing of the country” (Raina Summerson, Group CEO, Agincare) and providers are looking at how to mitigate attrition rates and keep services operating. What is clear is that an effective staff retention strategy is key to business success and should be a priority for care leaders. By improving retention, recruitment should also become less of an issue.

Improved communication and engagement with existing staff is an area in which providers have seen improved morale, culture and retention. Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends, feels that “more two-way communication with care workers, making them feel involved and involving them in the problem-solving” is critical to organisational success. This comes at an opportune time for social care providers – the stress and emergency of the pandemic has brought teams closer together than ever before and providers can harness this energy into a collaborative workforce.

How managers handle absence, mental health, grievances and performance, for example, all have a critical impact on the culture of the organisation and retention rates.

Creating a positive cohesive workplace culture where staff feel valued and have a voice is critical. Particular focus should also be paid to retaining new joiners. The cost of recruitment is high and with existing barriers to recruitment, it is imperative that once recruited, providers focus on effective onboarding and induction to limit attrition in the high risk first 90-day period. Statistically this been very high, with a previous study by Neil Eastwood across self-funder and local authority funded operations seeing around 48% attrition during this period.

Many providers are also assessing the training and support they offer managers, particularly around people management. Managers tend to have a broad range of responsibilities and often don’t receive the formal training and support required to effectively manage their teams. How they handle absence, mental health, grievances and performance, for example, all have a critical impact on the culture of the organisation and retention rates, so providers are seeking to upskill their managers in these areas.

Retaining a tired workforce – reinvigorating teams

Social care providers have had a challenging period, not just from a business perspective where they have had to pivot quickly to new ways of working and increased levels of health and safety considerations, but critically from a workforce perspective too.

Front and centre of this has been workforce fatigue. Throughout the pandemic, the toll on the social care workforce has been widely reported. Providers have commented on the incredible lengths that their staff have gone to and the pride the sector felt battling through an incredibly difficult period. That said, now that the emergency period is less pronounced, providers are seeing the underlying stress of the experience coming through. Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development at Oakland Care, has seen a step change in mental health issues across the sector and has noted an increase in sickness and “people resigning because they can no longer take the stress.”

58% of health and social care workers met the threshold for a mental health disorder and 22% met criteria for PTSD.

The fatigue the sector has been reporting is evidenced by the ‘Frontline-COVID study’ by the UCL-led COVID Trauma Response Working Group that found that after the first wave of COVID, 58% of health and social care workers met the threshold for a mental health disorder and 22% met criteria for PTSD .

This pressure on the workforce is exacerbated by economic considerations which have grown more severe in recent months with inflationary increases. There is a growing recognition that workforce “distress is around finances” (Neil Eastwood, CEO, Care Friends), with a significant increase in living costs, particularly energy, food, and petrol costs. This is borne out by the findings of the Care Workers Charity Impact Report (2021) which reported that “daily living costs still remains the most frequent use of our grants with 47% using the grant for that reason.” Economic pressures are adversely affecting attrition rates, with many workers looking at alternative careers to make ends meet. Raina Summerson, Group CEO of Agincare feels that “clearly the biggest headache for many operators is attracting and retaining the right staff and not losing them to hospitality and retail.” Whilst care staff are motivated by a myriad of factors including a sense of pride, giving back and a meaningful profession supporting people, the inability for care providers to compete on pay with the likes of Amazon, who are offering large sign-on bonuses and higher rates of pay, poses a real challenge to retaining staff. Recent reports indicate that some providers are trying to compete by increasing pay rates, one example being Vida Healthcare which announced a 30% pay rise taking hourly rates for care assistants to £12.32. Others have announced commitments to pay the Real Living Wage.

Clearly, the Government’s mandatory vaccination ‘experiment’ on the care home sector has not helped with retention. The impact of mandatory vaccinations is stark, with an estimated 40,000 workers leaving the sector at a time when recruitment and retention was a significant challenge. It was particularly damaging that the policy was not introduced to homecare services and the NHS at the same time, as unvaccinated staff left care homes to join those sectors.

Creating a positive cohesive workplace culture where staff feel valued and that they have a voice is critical.

This is further compromised by high levels of care home manager resignations, citing that they too are exhausted by the pressure and legal responsibilities that come with the role due to an ever-increasing focus on regulatory and inspection led agendas rather than focussing on care.

Despite the backdrop of increasing pressure on retaining staff in social care, Vic Rayner, CEO of the National Care Forum is quick to point out that “these are not new issues but clearly they’ve been highlighted and exacerbated over the last couple of years”. Staff attrition has had an operational and cost impact for providers and agency and recruitment costs have soared. The impact has been significant, with some providers needing to suspend care home admissions or hand back homecare contracts because they cannot recruit enough staff to run services safely.

The workforce pressures are also causing many independent owners involved in social care to reconsider their business investments, taking stock from the emergency of the pandemic to understand their business prospects and the future of the sector. Anecdotally we are hearing of provider owners who are as equally fatigued as workers. Whilst they couldn’t exit during the middle of COVID (nor indeed wanted to), John Lucas, Director at Hazlewoods, feels that “over next 12 months there will be a lot of people thinking that they want to exit.”

Mei-LingHuang - Partner, Social Care, RWK Goodman

Despite these challenges, social care is “essential infrastructure underpinning the health and wellbeing of the country” (Raina Summerson, Group CEO, Agincare) and providers are looking at how to mitigate attrition rates and keep services operating. What is clear is that an effective staff retention strategy is key to business success and should be a priority for care leaders. By improving retention, recruitment should also become less of an issue.

Improved communication and engagement with existing staff is an area in which providers have seen improved morale, culture and retention. Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends, feels that “more two-way communication with care workers, making them feel involved and involving them in the problem-solving” is critical to organisational success. This comes at an opportune time for social care providers – the stress and emergency of the pandemic has brought teams closer together than ever before and providers can harness this energy into a collaborative workforce.

How managers handle absence, mental health, grievances and performance, for example, all have a critical impact on the culture of the organisation and retention rates.

Creating a positive cohesive workplace culture where staff feel valued and have a voice is critical. Particular focus should also be paid to retaining new joiners. The cost of recruitment is high and with existing barriers to recruitment, it is imperative that once recruited, providers focus on effective onboarding and induction to limit attrition in the high risk first 90-day period. Statistically this been very high, with a previous study by Neil Eastwood across self-funder and local authority funded operations seeing around 48% attrition during this period.

Many providers are also assessing the training and support they offer managers, particularly around people management. Managers tend to have a broad range of responsibilities and often don’t receive the formal training and support required to effectively manage their teams. How they handle absence, mental health, grievances and performance, for example, all have a critical impact on the culture of the organisation and retention rates, so providers are seeking to upskill their managers in these areas.

Emerging from the storm

Chapter two

Plugging the gaps - attracting workforce

The workforce strategy for providers will need to be a two-pronged approach focusing on both retention and recruitment.

This symbiotic consideration is one that Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends points out flagging that “recruitment and retention are so tightly bound together that when recruitment goes wrong, immediately the pressure is on retention.”

The fundamental problem that the sector is experiencing is that “we don’t have enough people to come and work in social care and we haven’t for a long time. It’s not a UK only issue, it’s a global issue” (Vic Rayner, CEO, National Care Forum). Not only is there a shortage of UK workers applying to work in social care but recruitment from overseas has also been severely restricted by Brexit. There has also been fierce competition for staff as the country transitioned out of the pandemic and the retail and hospitality sectors re-opened.

“we don’t have enough people to come and work in social care and we haven’t for a long time...

The simple fact is that the recruitment strategies that are in place now at a sector level are “not sustained, they’re not big enough” (Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare). Funding, greater engagement with the problem at a national level and giving providers the necessary tools and investment to implement their own solutions, could create greater opportunities.

The perception of working in social care, pay rates and working arrangements are big factors in recruitment. Many providers are also grappling with the difficulties of attracting workers when other sectors can provide ancillary benefits that are more difficult to offer the care workforce. One such example is flexible working. As Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare concedes “people are now expecting different things from their working life that don’t actually necessarily fit with the way social care operates.” Whilst there are some opportunities for flexible working within social care, flexible working isn’t appropriate for some employees who are “new in their careers and need a lot more support on a day-to-day basis” (Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development, Oakland Care).

...the sector has got “a massive challenge around how much we pay people”

The perception is that the sector needs a reboot and to be re-cast by reference to what attracts people to work in the sector - instilling a belief that this is not just about end-of-life care, it’s about people living their lives and enjoying it. Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum echoes this point and wants to “tell people about the dignity it is bringing to people’s lives” as that will be a catalyst to attract those who want to give back and do something that is values based in society.

Reward is of course high on the agenda. Put simply, the sector has got “a massive challenge around how much we pay people” (Vic Rayner, CEO, National Care Forum). For many there is a need for a root and branch review by the Government on how the health and social care service is funded and staff remunerated. At the very least, the sector needs a pay structure that “sees social care on more of a par with NHS” (Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare). The report by Community Integrated Care entitled ‘Unfair to Care: Understanding The Social Care Pay Gap and How to Close It’ found that many frontline care workers would need to be paid 39% more (nearly £7,000 per year) to match the pay of equivalent positions in the NHS and local authorities.

Providers are increasingly seeing the need to develop pathways for progression and wider improvements in terms and conditions to counter the issues around core pay. Aligned to progression is the link to education and for social care - it’s clear that more could be done here with a structure focus on “putting those plans down now that will help us in the future” (Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development, Oakland Care).

...it’s clear that more could be done here with a structure focused on “putting those plans down now that will help us in the future”

Linking with colleges provides an opportunity to engage with young people with a desire to do something meaningful with their careers. Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development at Oakland Care believes that the relationship with colleges should start earlier, with providers working collaboratively to ensure that “students come to providers for internships and work-placements.” Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum agrees, pointing out that the sector needs to do more to “represent social care as career of choice in the education sector.” Whilst links and partnerships used to be more extensive, the pandemic has obviously dented those processes and reinstating and developing them could be of paramount importance to the sector.

Providers are now re-engaging with those who left the sector because of mandatory vaccination policies, but the anticipation is that a high percentage of those who left may not come back either because the relationship has been irreparably damaged, or they have found new opportunities in another sector.

As a result, providers are increasingly looking to recruit from abroad to plug gaps in their workforce provision. Inevitably, Brexit has made this approach harder, although the Government has recently added care workers to the Shortage Occupation List, so that they can now be recruited from overseas in addition to senior care workers, nurses and care managers. The sheer volume of providers looking for additional workforce via this route is evident, with Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare surmising that “everyone is fishing in the same pond even if it’s internationally.”

Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development at Oakland Care recognised the issues with the sponsorship application and conceded that “we’re trying to use it but whether or not we can actually recruit anyone from that route remains to be seen.” Once again though, remuneration raises its head here with many workers coming to the sector via this route not being able to source accommodation, living expenses and travel independently on the sector wage, leaving providers incurring significant costs to support overseas recruitment. Inevitably these costs are more of barrier when recruiting for less senior roles.

Plugging the gaps - attracting workforce

The workforce strategy for providers will need to be a two-pronged approach focusing on both retention and recruitment.

This symbiotic consideration is one that Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends points out flagging that “recruitment and retention are so tightly bound together that when recruitment goes wrong, immediately the pressure is on retention.”

The fundamental problem that the sector is experiencing is that “we don’t have enough people to come and work in social care and we haven’t for a long time. It’s not a UK only issue, it’s a global issue” (Vic Rayner, CEO, National Care Forum). Not only is there a shortage of UK workers applying to work in social care but recruitment from overseas has also been severely restricted by Brexit. There has also been fierce competition for staff as the country transitioned out of the pandemic and the retail and hospitality sectors re-opened.

“we don’t have enough people to come and work in social care and we haven’t for a long time...

The simple fact is that the recruitment strategies that are in place now at a sector level are “not sustained, they’re not big enough” (Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare). Funding, greater engagement with the problem at a national level and giving providers the necessary tools and investment to implement their own solutions, could create greater opportunities.

The perception of working in social care, pay rates and working arrangements are big factors in recruitment. Many providers are also grappling with the difficulties of attracting workers when other sectors can provide ancillary benefits that are more difficult to offer the care workforce. One such example is flexible working. As Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare concedes “people are now expecting different things from their working life that don’t actually necessarily fit with the way social care operates.” Whilst there are some opportunities for flexible working within social care, flexible working isn’t appropriate for some employees who are “new in their careers and need a lot more support on a day-to-day basis” (Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development, Oakland Care).

...the sector has got “a massive challenge around how much we pay people”

The perception is that the sector needs a reboot and to be re-cast by reference to what attracts people to work in the sector - instilling a belief that this is not just about end-of-life care, it’s about people living their lives and enjoying it. Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum echoes this point and wants to “tell people about the dignity it is bringing to people’s lives” as that will be a catalyst to attract those who want to give back and do something that is values based in society.

Reward is of course high on the agenda. Put simply, the sector has got “a massive challenge around how much we pay people” (Vic Rayner, CEO, National Care Forum). For many there is a need for a root and branch review by the Government on how the health and social care service is funded and staff remunerated. At the very least, the sector needs a pay structure that “sees social care on more of a par with NHS” (Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare). The report by Community Integrated Care entitled ‘Unfair to Care: Understanding The Social Care Pay Gap and How to Close It’ found that many frontline care workers would need to be paid 39% more (nearly £7,000 per year) to match the pay of equivalent positions in the NHS and local authorities.

Providers are increasingly seeing the need to develop pathways for progression and wider improvements in terms and conditions to counter the issues around core pay. Aligned to progression is the link to education and for social care - it’s clear that more could be done here with a structure focus on “putting those plans down now that will help us in the future” (Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development, Oakland Care).

...it’s clear that more could be done here with a structure focused on “putting those plans down now that will help us in the future”

Linking with colleges provides an opportunity to engage with young people with a desire to do something meaningful with their careers. Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development at Oakland Care believes that the relationship with colleges should start earlier, with providers working collaboratively to ensure that “students come to providers for internships and work-placements.” Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum agrees, pointing out that the sector needs to do more to “represent social care as career of choice in the education sector.” Whilst links and partnerships used to be more extensive, the pandemic has obviously dented those processes and reinstating and developing them could be of paramount importance to the sector.

Providers are now re-engaging with those who left the sector because of mandatory vaccination policies, but the anticipation is that a high percentage of those who left may not come back either because the relationship has been irreparably damaged, or they have found new opportunities in another sector.

As a result, providers are increasingly looking to recruit from abroad to plug gaps in their workforce provision. Inevitably, Brexit has made this approach harder, although the Government has recently added care workers to the Shortage Occupation List, so that they can now be recruited from overseas in addition to senior care workers, nurses and care managers. The sheer volume of providers looking for additional workforce via this route is evident, with Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare surmising that “everyone is fishing in the same pond even if it’s internationally.”

Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development at Oakland Care recognised the issues with the sponsorship application and conceded that “we’re trying to use it but whether or not we can actually recruit anyone from that route remains to be seen.” Once again though, remuneration raises its head here with many workers coming to the sector via this route not being able to source accommodation, living expenses and travel independently on the sector wage, leaving providers incurring significant costs to support overseas recruitment. Inevitably these costs are more of barrier when recruiting for less senior roles.

Emerging from the storm

Chapter three

The funding conundrum

Many of the problems articulated in this report point back to funding. Unlike other industries that are also in a state of flux and navigating a myriad of issues driving up costs and inflation, it remains that “they can easily pass the cost on to their consumers, but it’s more difficult for social care” (Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends).

The market cap on social care will be a significant moment in the provision of social care and will aim to address a system in desperate need of review. It is also a moment “about market signalling what the Government could do but also funding that change in the appropriate way” (Vic Rayner, CEO, National Care Forum).

Central to these changes in funding will be an opportunity to benchmark what kind of care people are looking for and to determine the structure of the sector in the future.

“the bigger operators and more profitable operators might be able to absorb some of that and weather the storm but that’s not a long-term solution.”

These decisions will have significant repercussions for the sector that needs more investment due to rising costs. Rachael Anstee, Partner at Hazlewoods, is seeing this discussion become more and more pointed amongst providers and believes that “the bigger operators and more profitable operators might be able to absorb some of that and weather the storm but that’s not a long-term solution.” Smaller operators though are not going to be able to manage the increasing cost of social care. Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum doesn’t “think we’re anywhere near having an honest conversation with the public about what that looks like”. Some we spoke with as part of the development of this report even wonder whether consultation around ‘fair cost’ will ever deliver due to such variances between providers and sub-sectors which makes one calculation impossible to derive.

“the recruitment and retention crisis and workforce is all very local, and so the councils have a role to play, as do the associations"

Much of this underlines the importance of an integrated health and social care provision. This is even more pointed when considering that some provider budgets will look better in the short-term due to government support as part of COVID that will fall away over time. However, the Government’s movement to an ICS structure paves the way for a more cohesive health system at a local level. The perception is that funding needs to be built with the entire health and social care provision in scope – looking at it in individual segments is not going to create opportunities that do not impact other areas of the ecosystem.

Mei-Ling Huang - Partner, Social Care, RWK Goodman

The ICS structure has re-opened the debate about who pays for care. As Neil Eastwoood, CEO of Care Friends flags “the recruitment and retention crisis and workforce is all very local, and so the councils have a role to play, as do the associations”. Therefore greater thought needs to be given to the respective funding streams available to all providers in that ecosystem. The unlocking of local structures is critical in making this work. The pressures that exist will need collaboration between all the respective stakeholders at a local level – decisions on where to target funding will need to be considered carefully to ensure health and social care providers provide a holistic offering, targeting the areas that matter and, in turn, improving workforce attraction, engagement and commitment.

The sector needs to work collaboratively to understand the interlinking objectives and aims of other providers in the sector and across all of health and social care provision. This requires a step change from the fragmented sector ‘as is’ into a collaborative model the likes of which the ICS is striving to achieve. For social care “there is a lack of cohesion in lobbying which restricts the ability of the sector to get what it deserves” (John Lucas, Director, Hazlewoods) and improving that will be critical to rebalance how we commission at a social care level. Even with targeted analysis and consideration of social care provision at a local level, it is also acknowledged that greater optimisation and engagement with technology may help narrow the funding deficit in the long-term.

The funding conundrum

Many of the problems articulated in this report point back to funding. Unlike other industries that are also in a state of flux and navigating a myriad of issues driving up costs and inflation, it remains that “they can easily pass the cost on to their consumers, but it’s more difficult for social care” (Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends).

The market cap on social care will be a significant moment in the provision of social care and will aim to address a system in desperate need of review. It is also a moment “about market signalling what the Government could do but also funding that change in the appropriate way” (Vic Rayner, CEO, National Care Forum).

Central to these changes in funding will be an opportunity to benchmark what kind of care people are looking for and to determine the structure of the sector in the future.

“the bigger operators and more profitable operators might be able to absorb some of that and weather the storm but that’s not a long-term solution.”

These decisions will have significant repercussions for the sector that needs more investment due to rising costs. Rachael Anstee, Partner at Hazlewoods, is seeing this discussion become more and more pointed amongst providers and believes that “the bigger operators and more profitable operators might be able to absorb some of that and weather the storm but that’s not a long-term solution.” Smaller operators though are not going to be able to manage the increasing cost of social care. Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum doesn’t “think we’re anywhere near having an honest conversation with the public about what that looks like”. Some we spoke with as part of the development of this report even wonder whether consultation around ‘fair cost’ will ever deliver due to such variances between providers and sub-sectors which makes one calculation impossible to derive.

“the recruitment and retention crisis and workforce is all very local, and so the councils have a role to play, as do the associations"

Much of this underlines the importance of an integrated health and social care provision. This is even more pointed when considering that some provider budgets will look better in the short-term due to government support as part of COVID that will fall away over time. However, the Government’s movement to an ICS structure paves the way for a more cohesive health system at a local level. The perception is that funding needs to be built with the entire health and social care provision in scope – looking at it in individual segments is not going to create opportunities that do not impact other areas of the ecosystem.

Mei-Ling Huang - Partner, Social Care, RWK Goodman

The ICS structure has re-opened the debate about who pays for care. As Neil Eastwoood, CEO of Care Friends flags “the recruitment and retention crisis and workforce is all very local, and so the councils have a role to play, as do the associations”. Therefore greater thought needs to be given to the respective funding streams available to all providers in that ecosystem. The unlocking of local structures is critical in making this work. The pressures that exist will need collaboration between all the respective stakeholders at a local level – decisions on where to target funding will need to be considered carefully to ensure health and social care providers provide a holistic offering, targeting the areas that matter and, in turn, improving workforce attraction, engagement and commitment.

The sector needs to work collaboratively to understand the interlinking objectives and aims of other providers in the sector and across all of health and social care provision. This requires a step change from the fragmented sector ‘as is’ into a collaborative model the likes of which the ICS is striving to achieve. For social care “there is a lack of cohesion in lobbying which restricts the ability of the sector to get what it deserves” (John Lucas, Director, Hazlewoods) and improving that will be critical to rebalance how we commission at a social care level. Even with targeted analysis and consideration of social care provision at a local level, it is also acknowledged that greater optimisation and engagement with technology may help narrow the funding deficit in the long-term.

Emerging from the storm

Chapter four

Technology and regulation –inhibitor or enabler?

The current workforce and funding issues the sector finds itself facing are likely to be difficult to surmount without further progression of the digital improvements that were realised at pace throughout the pandemic.

The development of voice activated applications, medication prompting and sensor-based technology to enable remote monitoring - to name just a few - have the potential to support new forms of care.

Despite these advances, there are still a number of barriers to engagement and a degree of realism is required in regard to the compatibility of advanced technology in a largely personalised care service. Recent reform papers have called for 80% of care services to be on electronic care planning systems but it is unclear whether this an achievable outcome in the short-term. Many providers had innovation high on their list before the pandemic but as we exit the pandemic, the focus is back on safety and risk, as increased scrutiny and compliance action from the CQC returns to health and social care provision.

“[is] there anything out there that’s actually cutting the number of staff you need by using technology?”

As Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends comments “the challenge really is implementing technology into a sector that is risk averse” and will continue to be. Whilst the use of video conferencing has been a massive innovation in the sector, there is still scepticism and room for improvement. Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development at Oakland Care agrees, pointing out that technology “has helped to work slightly smarter but it’s only as good as what you’re putting into it.” Whilst there had been a revolution in some areas, such as roster systems, we need to fully realise how and what approach we can take to answer the question that John Lucas, Director at Hazlewoods poses, namely whether “there is anything out there that’s actually cutting the number of staff you need by using technology .”

Mei-Ling Huang - Partner, Social Care, RWK Goodman

For this to happen, technology and social care need to work collaboratively. Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum sees a role for social care “to educate those technology suppliers about what the future’s likely to look like and how we need them to play a proper part in making all those things accessible and available for people who want to live life as independently as possible.”

As it stands, there is a perception that too often the relationship with CQC moves quickly to a position of challenge.

The regulator’s role in technology needs to be articulated and give providers an understanding of how this data can be used for it to be the enabler the sector would like. Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare, feels that at times there is a disconnect with front line service and that the CQC relationship feels “more distant, more risk based,” but perhaps positive collaboration and consistency on technology can be an enabler to better care and better regulation.

This enabler could be important to changing the relationship between providers and the CQC with a focus on moving inspections into a more positive engagement. Inspections shouldn’t start as an assumption of guilt and should instead be seen as “a chance to shine and show what you do” (Raina Summerson, CEO, Agincare). CQC are increasingly moving away from a comprehensive inspection approach to a model focused on feedback, local data and insight from third parties, which will put technology front and centre of the review.

As it stands, there is a perception that too often the relationship with CQC moves quickly to a position of challenge. Recent changes and this increasing enforcement trend is fueling a strained relationship and we need to focus as Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum suggests on “how you drive improvements and how you drive innovation.” The CQC’s position on using third-party data and what that data will look like continues to add substance to an increased role of data-focused oversight, but the question marks over reliability and confidence will need to be surmounted for the CQC / provider relationship to improve. It is imperative that there is a two-way conversation about the data that CQC relies on, not only to ensure the accuracy of ratings, but also to foster improvements and innovation that will bring the sector forward. An over-emphasis on risk is not helpful in creating an environment in which people can find new and better ways of doing things. Providers and managers need to have the headspace to be able to develop creative solutions.

Inspections shouldn’t start as an assumption of guilt and should instead be seen as “a chance to shine and show what you do”

As well as narrowing the volume of work that social care needs to preside over, technology and the Internet of Things can increase independence and help provide a form of care that is more suited to the individual concerned. Technology may also help support independent living and people's dignity via remote monitoring and as Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends points out that technology can “be easily employed to improve communication and overcome isolation.” For workforce, technology can help reduce physically demanding tasks and low-level administrative duties, thereby supporting staff’s wellbeing, enabling them to work at their highest skill level, and have higher quality contact with clients.

Despite the opportunities presented, there is also a sense of realism about the need to develop skill sets and sufficient funding to enable the use of technological solutions to derive improvements in care. Technology is part of the solution but the focus also needs to stay on people and that includes the regulator’s approach to their assessments of care provision if we are to create an environment in which innovation can help our sector thrive.

Technology and regulation –inhibitor or enabler?

The current workforce and funding issues the sector finds itself facing are likely to be difficult to surmount without further progression of the digital improvements that were realised at pace throughout the pandemic.

The development of voice activated applications, medication prompting and sensor-based technology to enable remote monitoring - to name just a few - have the potential to support new forms of care.

Despite these advances, there are still a number of barriers to engagement and a degree of realism is required in regard to the compatibility of advanced technology in a largely personalised care service. Recent reform papers have called for 80% of care services to be on electronic care planning systems but it is unclear whether this an achievable outcome in the short-term. Many providers had innovation high on their list before the pandemic but as we exit the pandemic, the focus is back on safety and risk, as increased scrutiny and compliance action from the CQC returns to health and social care provision.

“[is] there anything out there that’s actually cutting the number of staff you need by using technology?”

As Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends comments “the challenge really is implementing technology into a sector that is risk averse” and will continue to be. Whilst the use of video conferencing has been a massive innovation in the sector, there is still skepticism and room for improvement. Mo Quadri, Director of People and Organisational Development at Oakland Care agrees, pointing out that technology “has helped to work slightly smarter but it’s only as good as what you’re putting into it.” Whilst there had been a revolution in some areas, such as roster systems, we need to fully realise how and what approach we can take to answer the question that John Lucas, Director at Hazlewoods poses, namely whether “there is anything out there that’s actually cutting the number of staff you need by using technology .”

Mei-Ling Huang - Partner, Social Care, RWK Goodman

For this to happen, technology and social care need to work collaboratively. Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum sees a role for social care “to educate those technology suppliers about what the future’s likely to look like and how we need them to play a proper part in making all those things accessible and available for people who want to live life as independently as possible.”

As it stands, there is a perception that too often the relationship with CQC moves quickly to a position of challenge.

The regulator’s role in technology needs to be articulated and give providers an understanding of how this data can be used for it to be the enabler the sector would like. Raina Summerson, CEO of Agincare, feels that at times there is a disconnect with front line service and that the CQC relationship feels “more distant, more risk based,” but perhaps positive collaboration and consistency on technology can be an enabler to better care and better regulation.

This enabler could be important to changing the relationship between providers and the CQC with a focus on moving inspections into a more positive engagement. Inspections shouldn’t start as an assumption of guilt and should instead be seen as “a chance to shine and show what you do” (Raina Summerson, CEO, Agincare). CQC are increasingly moving away from a comprehensive inspection approach to a model focused on feedback, local data and insight from third parties, which will put technology front and centre of the review.

As it stands, there is a perception that too often the relationship with CQC moves quickly to a position of challenge. Recent changes and this increasing enforcement trend is fueling a strained relationship and we need to focus as Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum suggests on “how you drive improvements and how you drive innovation.” The CQC’s position on using third-party data and what that data will look like continues to add substance to an increased role of data-focused oversight, but the question marks over reliability and confidence will need to be surmounted for the CQC / provider relationship to improve. It is imperative that there is a two-way conversation about the data that CQC relies on, not only to ensure the accuracy of ratings, but also to foster improvements and innovation that will bring the sector forward. An over-emphasis on risk is not helpful in creating an environment in which people can find new and better ways of doing things. Providers and managers need to have the headspace to be able to develop creative solutions.

Inspections shouldn’t start as an assumption of guilt and should instead be seen as “a chance to shine and show what you do”

As well as narrowing the volume of work that social care needs to preside over, technology and the Internet of Things can increase independence and help provide a form of care that is more suited to the individual concerned. Technology may also help support independent living and people's dignity via remote monitoring and as Neil Eastwood, CEO of Care Friends points out that technology can “be easily employed to improve communication and overcome isolation.” For workforce, technology can help reduce physically demanding tasks and low-level administrative duties, thereby supporting staff’s wellbeing, enabling them to work at their highest skill level, and have higher quality contact with clients.

Despite the opportunities presented, there is also a sense of realism about the need to develop skill sets and sufficient funding to enable the use of technological solutions to derive improvements in care. Technology is part of the solution but the focus also needs to stay on people and that includes the regulator’s approach to their assessments of care provision if we are to create an environment in which innovation can help our sector thrive.

Concluding remarks

Concluding remarks

Collaboration is key – work together with a shared voice

Despite the challenges of recent years, social care provision has had to change and many are positive about this. As Vic Rayner (CEO of National Care Forum) commented, the sector has ”shown that we can flex and move at speed”. Harnessing this capacity and desire for change is critical to further improvement in the sector. To achieve this the sector needs to work collaboratively and will need to have a shared voice with strategic, articulated and shared purpose to achieve the collective aims for the sector in society. Regional and national care associations must be allowed to play a pivotal role in driving change and shaping government policy.

Embracing change – harnessing opportunities for improvement

The sector needs to continue to adapt and develop to meet the evolving demands of the people they support and the current challenging business environment. This needs to be supported through government policy, local government commissioning and appropriate regulatory oversight in order to drive innovation and, critically, the sharing of innovation for the improvement of the sector. Appetite for growth from larger providers “might be accelerating, because they need to show growth that is more difficult organically” (John Lucas, Director Hazlewoods) but at a wider level the sector needs to embrace technological developments that have moved at a pace in recent years, to improve.

Let’s not lose focus on what we want to achieve – good care

The sector has come through a very difficult period with a multitude of reasons why many in the sector feel exhausted and burnt out. Despite this, the sector is buoyed by the continual desire for those engaged to provide good care and to ensure that those in their care “have fantastic fulfilling lives at whatever age they are” (Vic Rayner, CEO of National Care Forum). The sector needs to continue to harness this underlying principle in everything they do strategically from recruitment and retention policies to administrative and care quality provisions – it’s not about just about staff spending all their time doing record keeping – it’s about providing care and support and building relationships.

We would like to thank those who have contributed to this report and welcome you to join the discussion via the activities we have planned over the coming months.

Thank you to our panel of expert contributors.

Thank you to our panel of expert contributors.

Be part of the conversation by joining James Sage, Hazel Phillips and Mei-Ling Huang and other sector experts in our Emerging from the storm – the reflection series:

Podcast – Crisis Management in Social Care – featuring Charlie Jones of BKR Care Consultancy and Nathan Hollow of PLMR

Podcast – Social Care Insights – featuring Sophie Chester-Glyn of Coproduce Care

Webinar – Recruitment and retention – How to become an employer of choice and reduce staff turnover

Webinar – Data vs personalised care – are they mutually exclusive?

Podcast – Integrated care – does M&A play a part in the recovery?